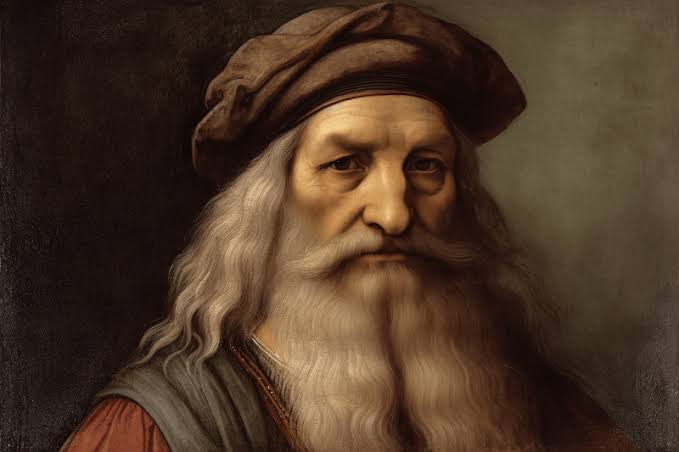

Leonardo da Vinci Biography

Born: April 15, 1452

Died: May 2, 1519

{Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on his achievements as a painter, he has also become known for his notebooks, in which he made drawings and notes on a variety of subjects, including anatomy, astronomy, botany, cartography, painting, and palaeontology. Leonardo is widely regarded to have been a genius who epitomised the Renaissance humanist ideal, and his collective works comprise a contribution to later generations of artists matched only by that of his younger contemporary Michelangelo.

Born out of wedlock to a successful notary and a lower-class woman in, or near, Vinci, he was educated in Florence by the Italian painter and sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio. He began his career in the city, but then spent much time in the service of Ludovico Sforza in Milan. Later, he worked in Florence and Milan again, as well as briefly in Rome, all while attracting a large following of imitators and students. Upon the invitation of Francis I, he spent his last three years in France, where he died in 1519. Since his death, there has not been a time where his achievements, diverse interests, personal life, and empirical thinking have failed to incite interest and admiration, making him a frequent namesake and subject in culture.

Leonardo is identified as one of the greatest painters in the history of Western art and is often credited as the founder of the High Renaissance. Despite having many lost works and fewer than 25 attributed major works – including numerous unfinished works – he created some of the most influential paintings in the Western canon. His magnum opus, the Mona Lisa, is his best known work and is the world’s most famous individual painting. The Last Supper is the most reproduced religious painting of all time and his Vitruvian Man drawing is also regarded as a cultural icon. In 2017, Salvator Mundi, attributed in whole or part to Leonardo, was sold at auction for US$450.3 million, setting a new record for the most expensive painting ever sold at public auction.

Revered for his technological ingenuity, he conceptualised flying machines, a type of armoured fighting vehicle, concentrated solar power, a ratio machine that could be used in an adding machine, and the double hull. Relatively few of his designs were constructed or were even feasible during his lifetime, as the modern scientific approaches to metallurgy and engineering were only in their infancy during the Renaissance. Some of his smaller inventions, however, entered the world of manufacturing unheralded, such as an automated bobbin winder and a machine for testing the tensile strength of wire. He made substantial discoveries in anatomy, civil engineering, hydrodynamics, geology, optics, and tribology, but he did not publish his findings and they had little to no direct influence on subsequent science.} From Wikipedia

VIDEO LESSON: Leonardo da Vinci

Why do we do copies after Old Masters, such as Leonardo da Vinci? We draw and paint copies of previous masters so that we can learn. But to learn, we have to risk failure, and we have to be comfortable with evolving the idea of the copy. And so, when I draw this copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Portrait of a Young Woman, I make a lot of mistakes- and I’m fine with it! After all, it isn’t about the pretty drawing on the piece of paper at the end, it’s about the process of exploring how a previous artist thought. It forces us to abandon preconceived notions of “how to draw a woman’s face” or “how to shade in portraiture.” Instead of holding on to our own notions, we have to abandon them to see how Leonardo did it- the delicate sfumato of the shade on the woman’s cheek, the crisp outline of the retina, the soft shading at the upturned corner of the mouth. So join me, as in pencil I do a copy after this silverpoint drawing by Leonardo. And don’t beat yourself up- allow yourself to erase and move your shapes around, until you find the harmony of shapes that Leonardo has so subtly depicted.